Hidden in a desolate side canyon on a steep mountainside above Death Valley, the remains of an aerial tramway trace a path across ridges on their way to a small mine above. Those who make this hike will find something else unexpected: not the remnants of a Bullfrog-era bonanza, but a monument to one family's struggle against this unforgiving land.

The remains of the mine cling to the mountainside in a place that seems almost impossible to work. At 3,000 feet long with 1,100 feet of vertical drop, the tramway is an impressive piece of engineering. Some of the double rope tram remains, including cables and towers, but the power cable is missing. We saw pieces of buried cable in the canyon bottom.

History

The King Midas claim sits about half a mile south of the famous Keane Wonder Mine, but the two operations share nothing but geography. While the Keane Wonder produced over a million dollars in gold during the Bullfrog boom of 1904-1916, the King Midas tells a quieter, more personal story of one family's struggle against the Funeral Mountains.

The mine's real history begins in 1949 when Michael Joseph Harris relocated the claims and set to work with his wife Patricia and son Jim. Harris sometimes called his operation the "Keane Wonder Extension," perhaps hoping some of that mine's luck would rub off. It didn't, but not for lack of effort.

The Harris family's most remarkable achievement was constructing a 3,000-foot aerial tramway that descended 1,100 vertical feet from the mine to the canyon floor. This was work normally done by professional mining crews with mules and equipment. The Harrises did it themselves.

The tramway consisted of galvanized cables strung between steel base towers, with a 4-cylinder Ford engine serving as the hoist at the top. Jim Harris, then a young man, marked his work on the first steel tower by arranging small stones in the concrete to spell "1949."

On March 4, 1950, they sent an Ingersoll-Rand air compressor (105 cfm) and a 4-cylinder engine up the tramway in pieces. The hoist drum's heavy weldment had to be carried on their backs from the canyon floor.

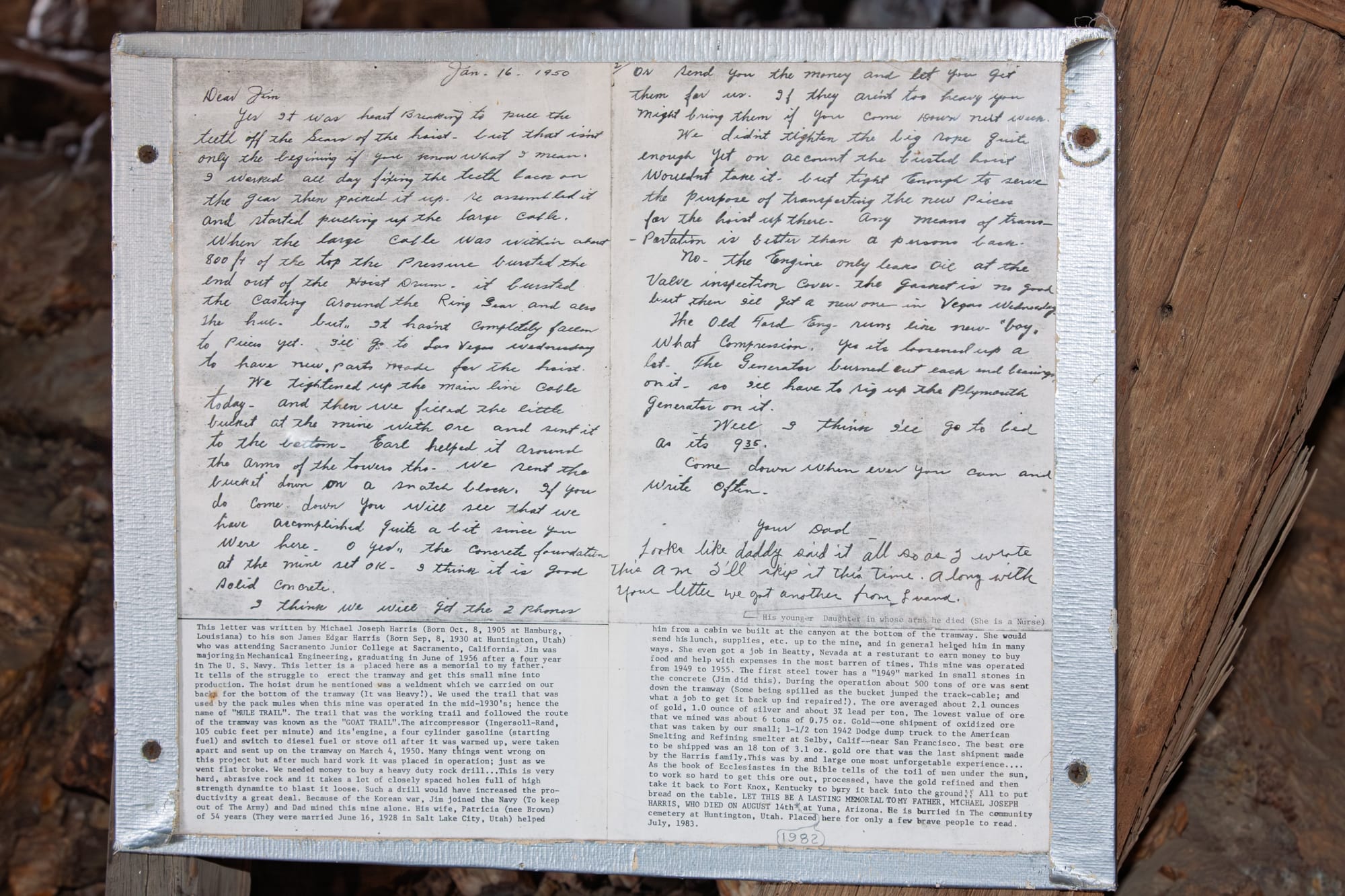

A January 16, 1950 letter from Michael Harris to his son Jim (then attending Sacramento Junior College studying mechanical engineering) reveals the constant setbacks they faced. The hoist drum had suffered a catastrophic failure, with pressure bursting the end out and breaking the casting around the ring gear. Harris had to drive to Las Vegas to have new parts fabricated.

The Ford engine, at least, was running well. Harris wrote that it "seems like new, boy, what compression," though a valve cover gasket was leaking. The generator had burned out its bearings, so he planned to rig a Plymouth generator instead. Despite everything, he reported successfully sending the first ore bucket down on a snatch block.

Patricia Harris worked at a restaurant in Beatty to earn money for food and mine expenses during what the family later called "the most barren of times." All water and supplies had to be hauled by truck from Beatty across the desert.

When the Korean War began, Jim Harris joined the Navy to avoid being drafted into the Army. After that, Michael Harris worked the mine alone.

Between 1949 and 1955, the Harrises sent approximately 500 tons of ore down the tramway. The ore came from veins cutting through the hard marble of the Crystal Springs formation. It averaged 2.1 ounces of gold, 1.0 ounce of silver, and about 3% lead per ton. Their best shipment was 18 tons grading 3.1 ounces of gold, which was also their last. The lowest value shipment was 6 tons of oxidized ore running only 0.75 ounces of gold.

All ore went to the American Smelting and Refining Company smelter at Selby, California, near San Francisco. Harris hauled it himself in a 1-1/2 ton 1942 Dodge dump truck.

The family "went flat broke" just as the operation was becoming functional. What they really needed was a heavy-duty rock drill to work the hard rock efficiently. They never got one.

In July 1983, Jim Harris returned to the King Midas and placed a memorial to his father at the mine site. Michael Joseph Harris had been born October 8, 1905, in Hamburg, Louisiana. He died August 14, 1982, in Yuma, Arizona, and was buried in Huntington, Utah.

The memorial contains a letter from his father along with a typed explanation of the family's history and their years of struggle in the Funeral Mountains. It quotes Ecclesiastes on the toil of men, noting the irony of mining gold only to refine it and bury it back at Fort Knox, all "to put bread on the table."

Jim's inscription reads: "LET THIS BE A LASTING MEMORIAL TO MY FATHER, MICHAEL JOSEPH HARRIS."

No mining has been done in the Funeral Mountains since the Harrises ceased operations in 1955. The area remains stark, harsh, and wonderfully desolate in that uniquely Death Valley kind of way.

I hiked up to the King Midas with friends Dan and Sharon in April 2008.

Getting There

Only GPS waypoints below, but you will need to find the trail that switchbacks up the eastern wall of the canyon to reach the mine. You can't reach the mine from the canyon bottom.